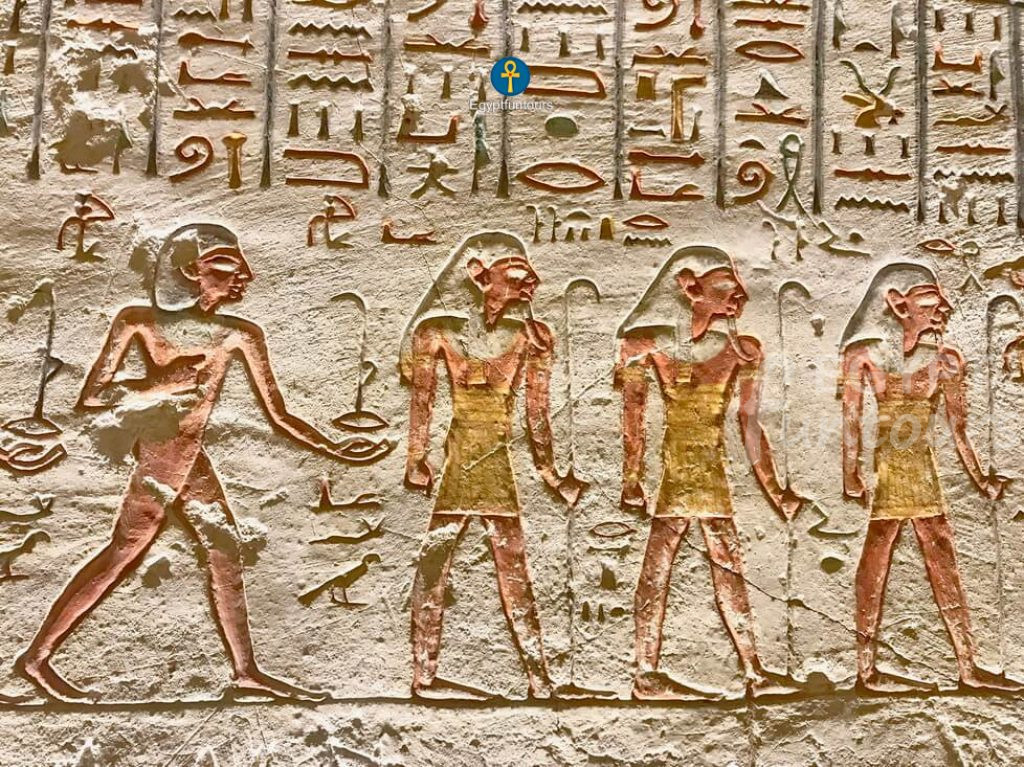

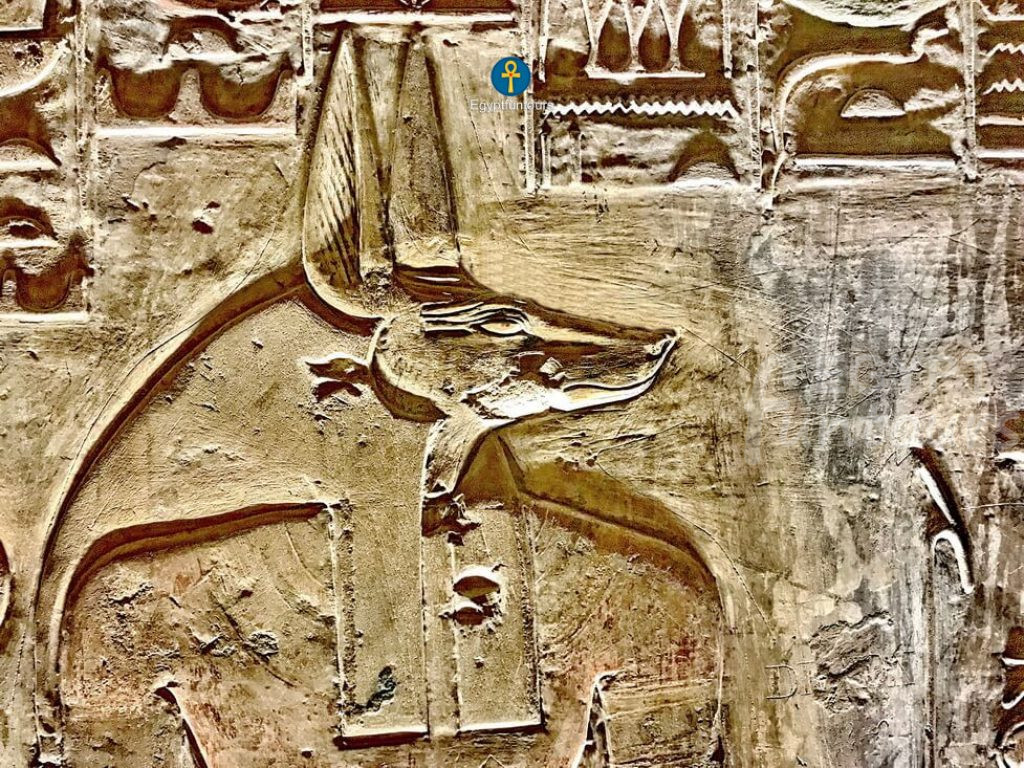

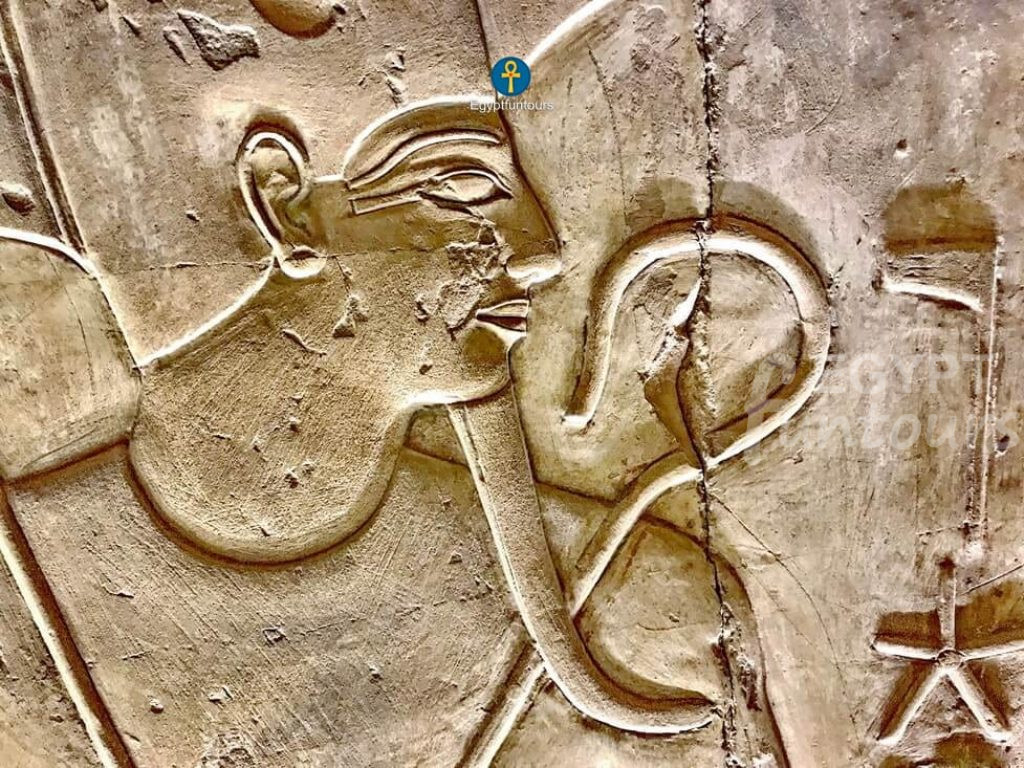

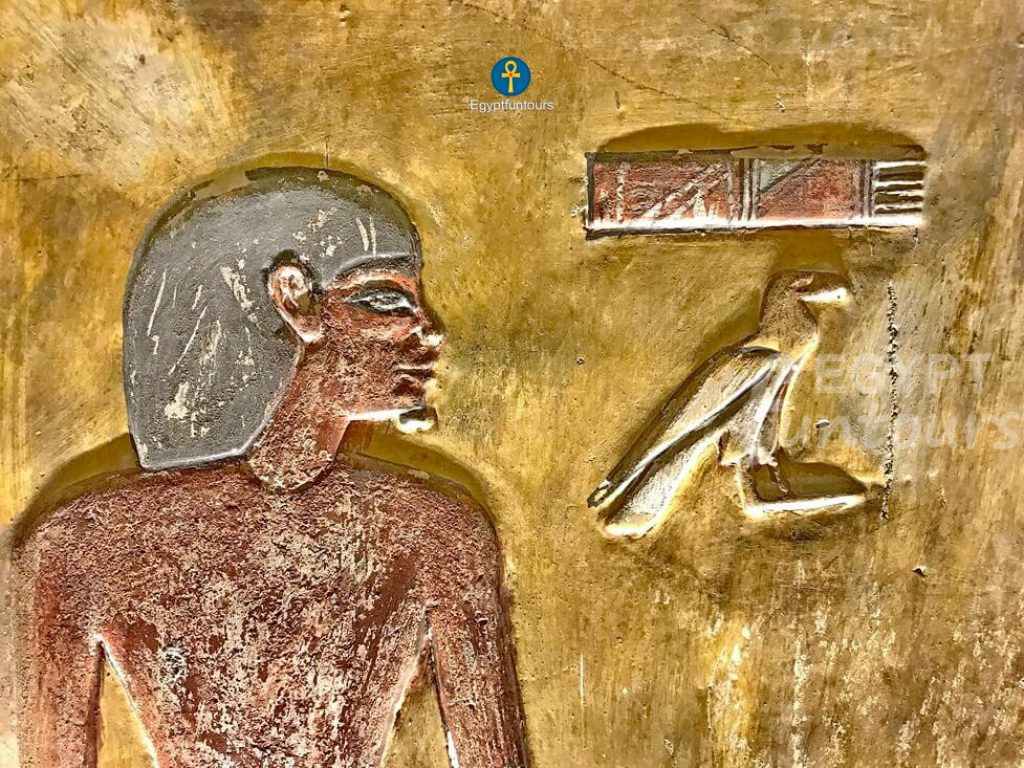

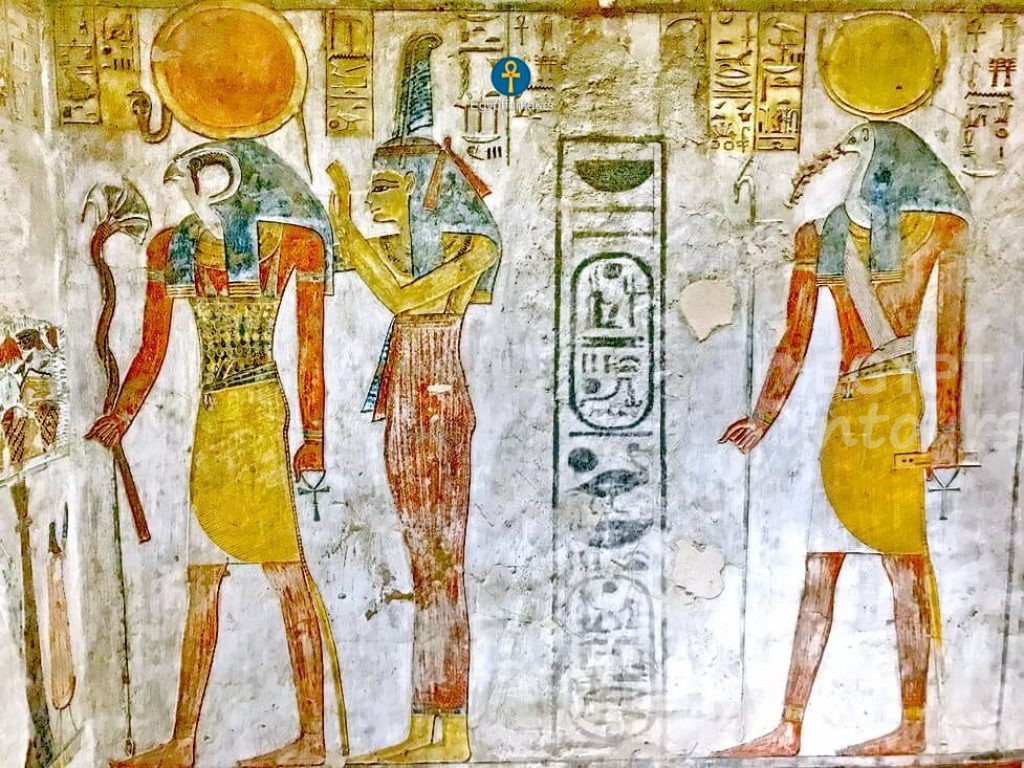

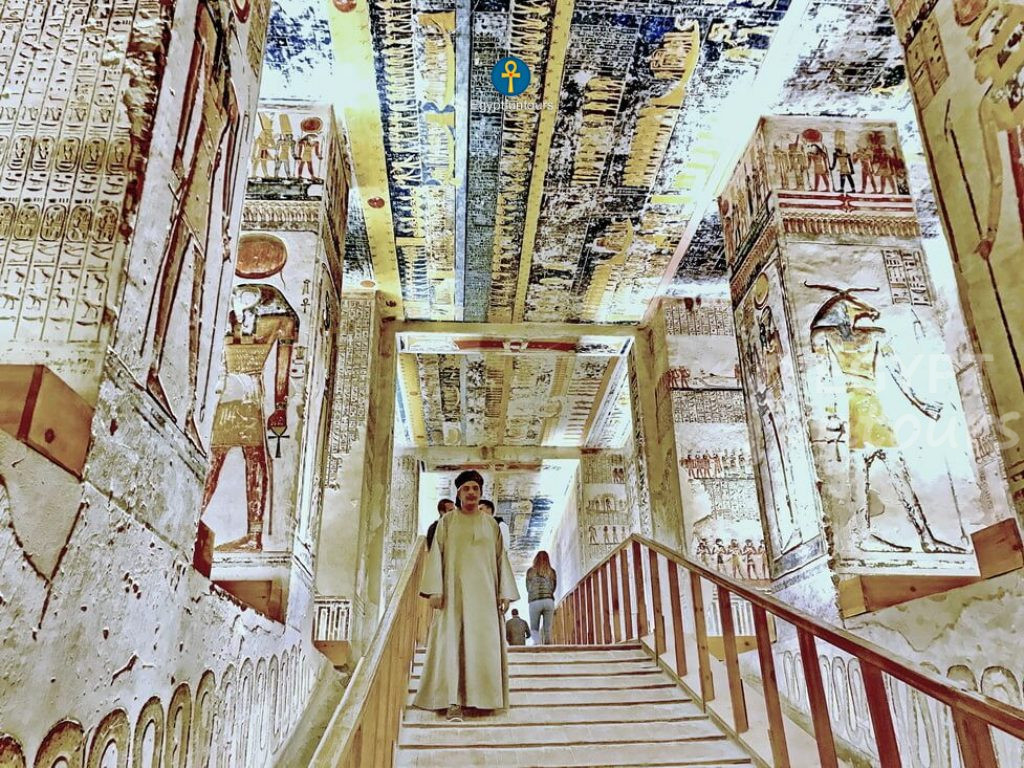

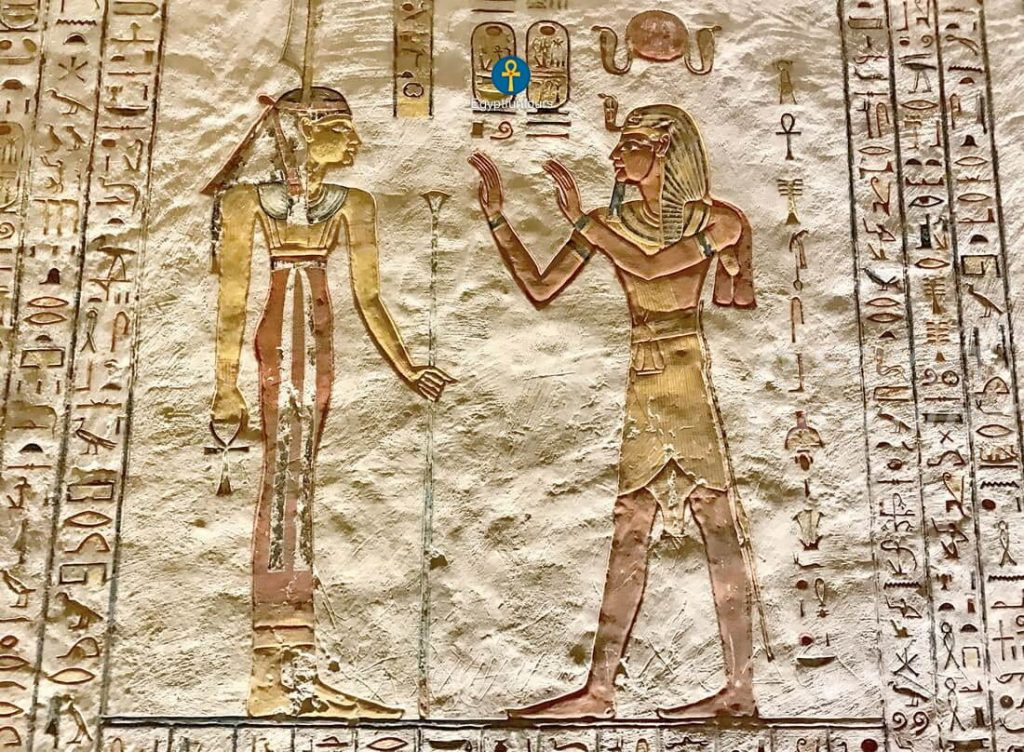

The road where God Ra “The Sun God” sets. The Kings of Egypt’s affluent New Kingdom (1550–1069 BC) were buried in a barren dry river valley across the Nile from Luxor, thus the Valley of the Kings’ current name.

The title “Valley of the kings” isn’t fully true, though, because certain members of the royal family other than the King, as well as a few non-royal, but extremely high-ranking, persons, were buried here as well. The East and West Valleys make up the Valley of the Kings. The eastern valley is by far the more famous of the two, with only a few graves in the western valley. In total, there are 65 tombs in the Valley of the Kings.

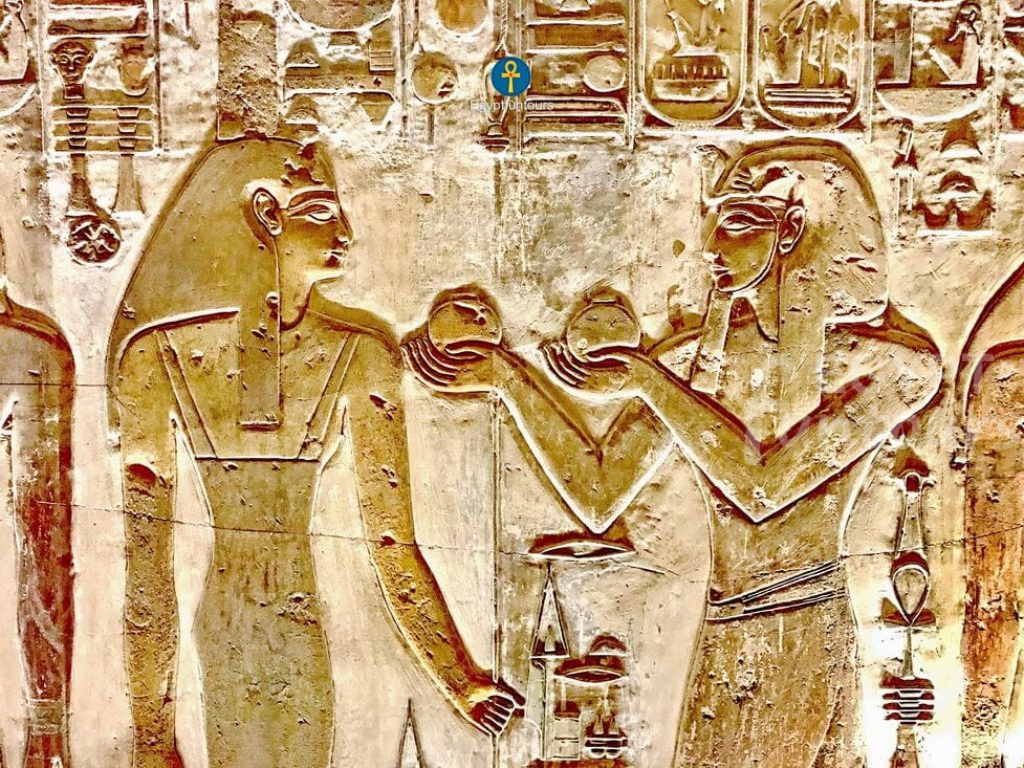

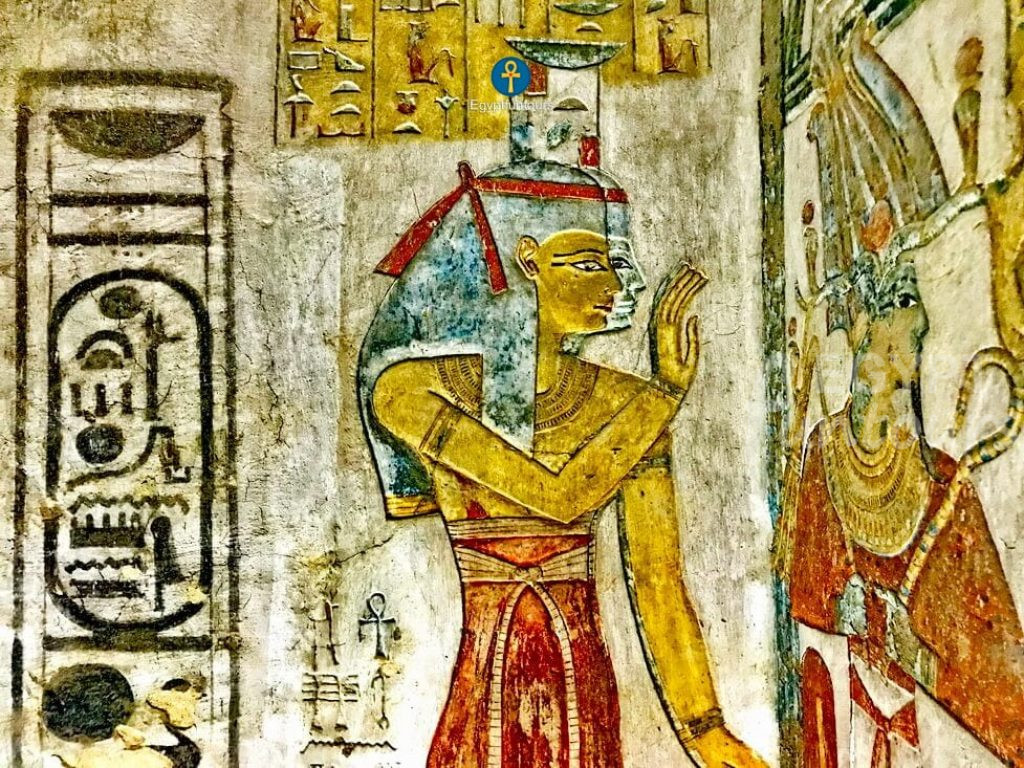

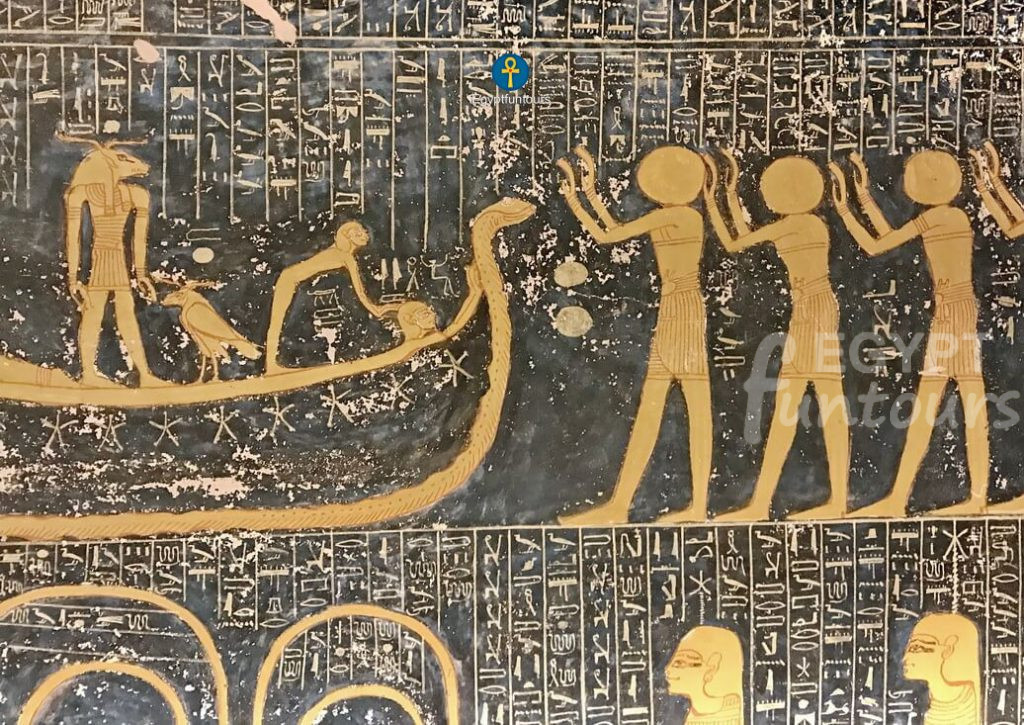

This royal burial ground’s location was chosen with great care. Its location on the west bank of the Nile is also noteworthy. The west acquired funeral connections since the sun god set (dead) in the western horizon before being resurrected, and regenerated, on the eastern horizon. For this reason, ancient Egyptian graves were mostly found on the Nile’s west bank.

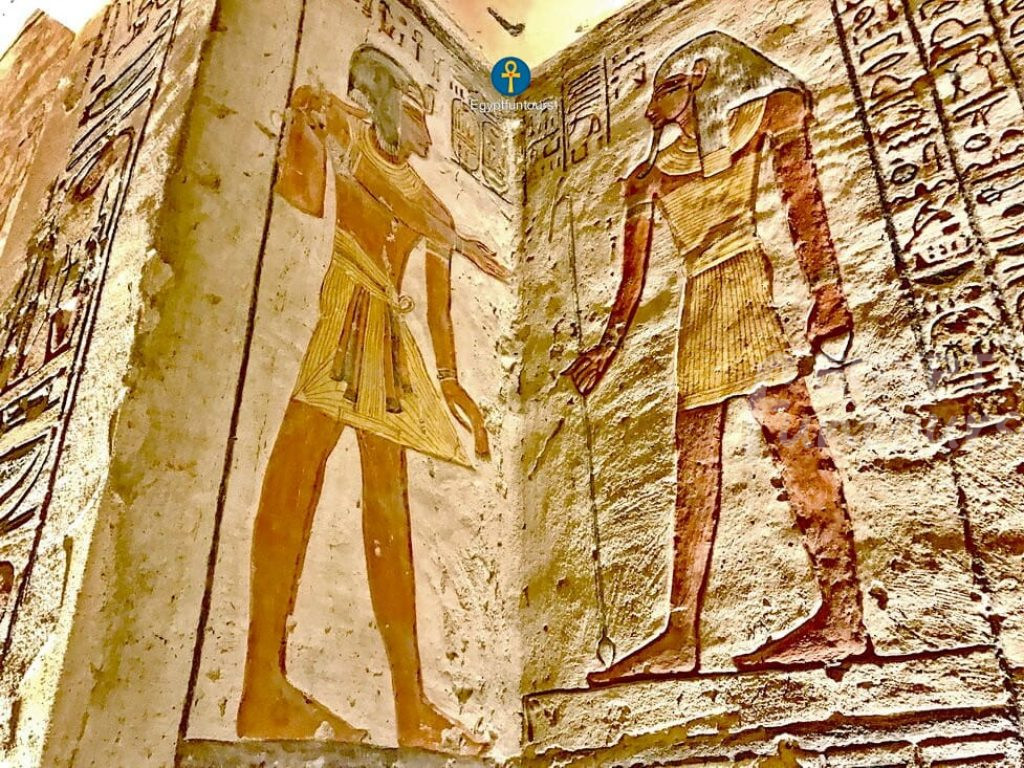

Under the shadow of a pyramid-shaped peak rising out of the rocks surrounding the valley, the New Kingdom’s strong rulers were put to rest. Even the exact valley in which the royal tombs were dug was not chosen at random. The pyramid represented renewal and hence perpetual life, and the existence of a natural pyramid was seen as a heavenly omen. The entire region, as well as the peak itself, was devoted to Hathor’s funeral aspect, the “Mistress of the West”.

The valley’s remote location was another factor in its selection as the king’s ultimate resting place. Even in ancient times, tomb thefts had a place. The Egyptians were well aware of this, as well as the fate of the Old and Middle Kingdom pyramids, and chose to bury their dead in secret, underground graves in a desert valley.

Thutmose I (c.1504–1492 BC), the third king of the Eighteenth Dynasty, was the first New Kingdom ruler to be buried in the Valley of the Kings. According to Ineni, the senior official in charge of his tomb’s excavation, “I oversaw the excavation of his Person’s [the king’s] cliff-tomb in secret; none seeing, none hearing”.

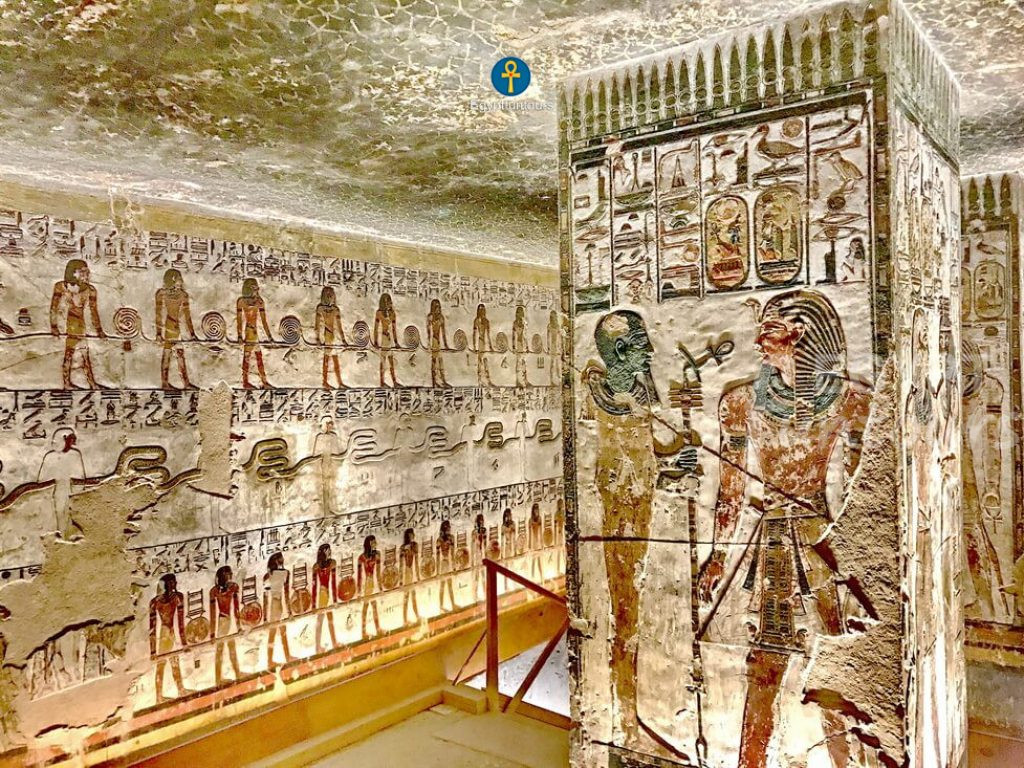

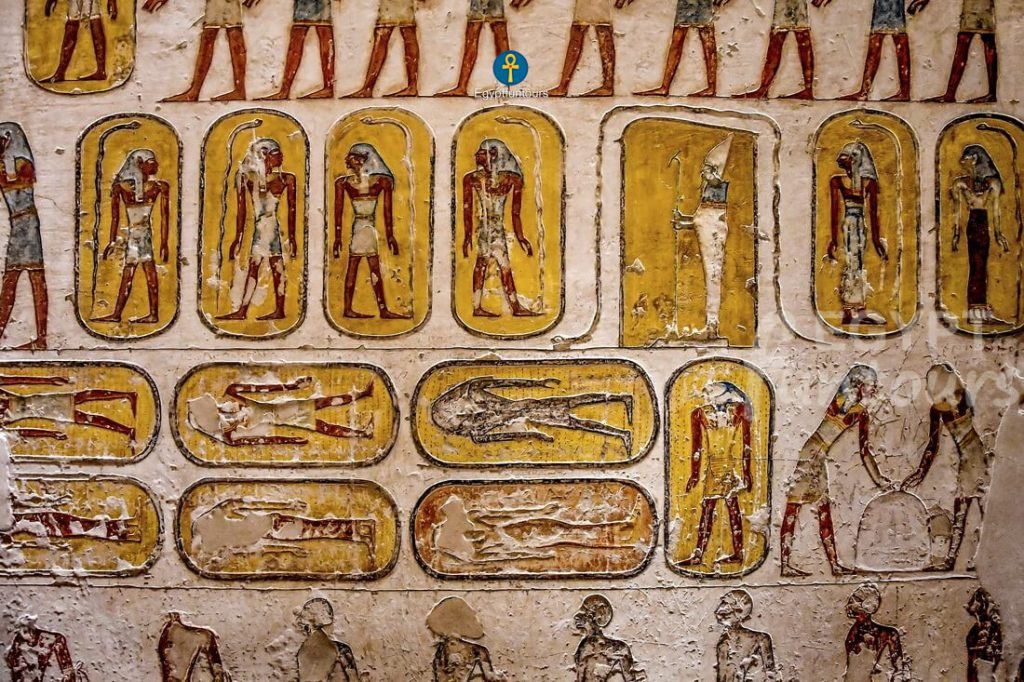

The bulk of the Valley of the Kings’ 65 numbered tombs may be classified as minor tombs, either because they have produced little information so far or because their explorers only kept a poor record of their findings. Some have gotten relatively little attention or have only been mentioned briefly. The majority of these tombs are tiny, with only a single burial chamber accessible through a shaft or stairway connected to the chamber by a hallway or series of corridors.

Nonetheless, some of the tombs are bigger and include numerous chambers. These small tombs were used for a variety of purposes: some were meant for graves of lower royalty or private funerals, some included animal remains, while others appeared to have never been buried at all. Many of these tombs also performed additional roles, and subsequently, intrusive material connected to these other activities has been discovered. While some of these graves have been exposed since antiquity, the bulk was discovered at the peak of the valley’s research in the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Tourism at the valley of kings:

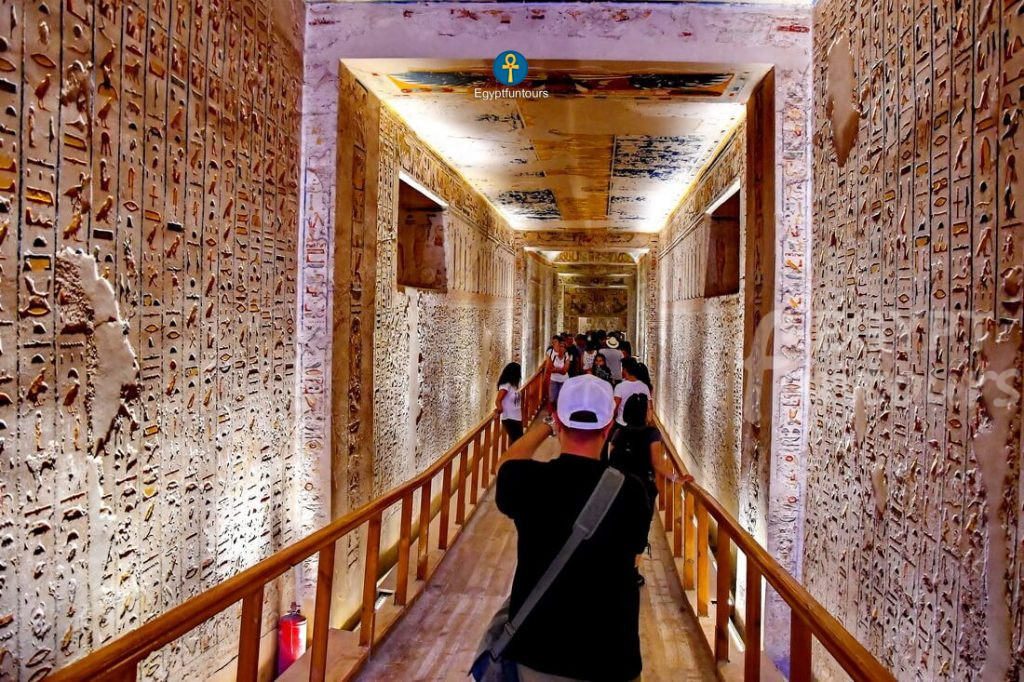

The majority of the tombs are closed to the public (18 are open to the public, but they are seldom open at the same time), and those that are open are periodically closed for repair work. Because of the high volume of visitors to KV62, there is now a separate fee for entering the tomb.

The only open tomb in the West Valley is that of Ay, which requires a special ticket. The tour guides are no longer permitted to provide lectures inside the tombs, and tourists are required to go through the tombs quietly and in a single line. This is done to cut down on time spent in the tombs and to keep crowds from harming the decoration’s surfaces.

The major valley attracts 4,000 to 5,000 people on most days of the week. Because there is just one tomb exposed to the public in the West Valley, it receives far fewer visitors.

Tomb robbers in the Valley of the Kings:

In 1922, KV62 (Tut’s Tomb) was discovered undisturbed.

Almost all of Egypt’s tombs have been looted. Several papyri have been discovered that relate to tomb robber trials. The majority of them are from the late Twentieth Dynasty. Papyrus Mayer B, for example, relates the theft of Ramesses VI’s tomb and was most likely written around Ramesses X’s eighth or ninth year, about 1118BC.

The script is 14 lines long and is based on the common hieratic of the twentieth century. It mentions a heist at Ramesses VI’s tomb. Sesamum, a foreigner, led us up and showed us King Ramesses VI’s tomb. And I spent four days breaking into it, with all five of us present. We entered the tomb after opening it. We discovered a bronze kettle and three bronze washbasins.

In confessing their misdeeds, the thief goes on to say that there was a minor squabble among the thieves over how to divide the treasures from the tomb evenly.

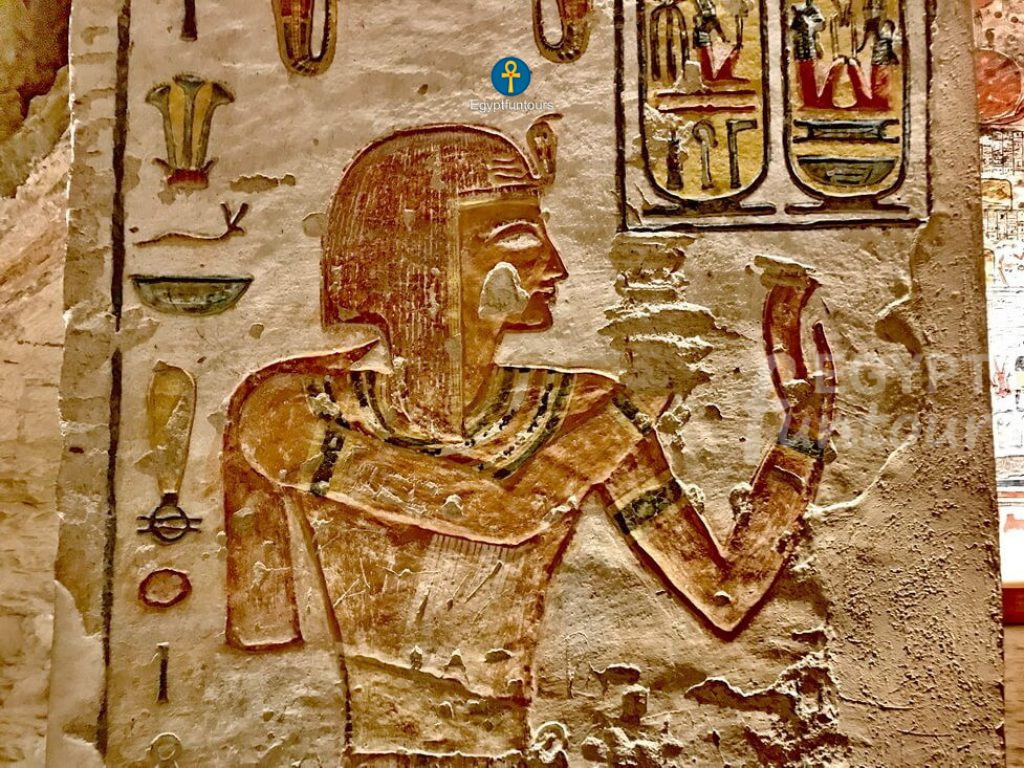

Tombs were full of treasures, making them a great target for robbery. Mummies’ rooms and bodies were frequently robbed for valuable metals and stones, the most prevalent of which were gold and silver, linens, and ointments or unguents. Because many of the items buried with the mummies were perishable, tombs were frequently stolen while still fresh.

Under the virtual civil war that began during Ramesses XI’s reign, the valley appears to have been subjected to government looting. The graves were uncovered, the riches were taken out, and the mummies were gathered into two huge caches. Others were hidden within Amenhotep I’s tomb, while one was found in the tomb of Amenhotep II. The majority of them were transported to the Deir el-Bahari cache a few years later, which included no less than forty royal corpses and their coffins.

During this time, only tombs whose sites had been lost (KV62, KV63, and KV46, though both KV62 and KV46, were looted shortly after their real closure) remained untouched.

The Pyramid of Giza, the oldest of the seven wonders of the world, was erected by King Khufu, the most powerful monarch of the Old Kingdom. To keep robbers from stealing the tomb in the biggest of the pyramids, a system of tunnels was built. According to sources, the pyramid remained unbroken by thieves until the ninth century AD, but once inside the King’s bedroom, the invaders saw the mummy had been stolen and the sarcophagus had been opened.

Tombs were raided not just for their contents, but also for their intended function. An empty tomb might be repurposed as a burial site for another mummy after it has been plundered, as happened in the smallest of Giza’s pyramids.

The Valley of the kings on Wikipedia