Ancient Egypt’s the Middle Kingdom Artistic Renaissance

The Middle Kingdom of Ancient Egypt is known as a period of transformation that occurred between 2040 and 1782 B.C.E. It is famous for the greatest works of literature, sculpture, and art that were unlike anything that had come before it and influenced this enlightenment to new heights, becoming the face of Egyptian culture in front of the world. When Egypt’s old monarchy fell, the middle kingdom emerged from its ashes to reclaim the grandeur of ancient Egypt.

If you want to enjoy a memorable holiday in Egypt, check out our gorgeous Egypt travel packages.

Egypt’s the Middle Kingdom Achievements

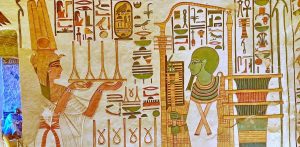

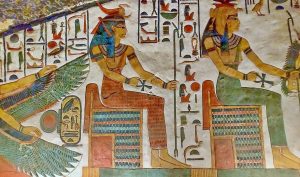

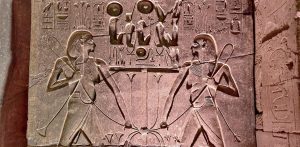

The Kingdom of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, often known as the golden era, witnessed numerous advancements and achievements in science and construction during the 12th dynasty, thanks to Mentuhotep the second, who, like Menes, reunified Egypt and ushered in the Middle Kingdom. When the Thebans dynasty triumphed and strengthened their dominance of the kingdom, Mentuhotep II was able to terminate the conflict between the tribes of Thebeans and Heracleapolitan. During the 11th dynasty, he and his forefathers chose “Thebes” as the capital and artistic center, and he also led military operations to Nubia and reestablished Egyptian sovereignty in Sinai. Luxor, which you may see during your Egypt trips, is now known as Thebes. Many gold and silver statues were created, as well as many works of literature that recorded all of the scientific and mathematical discoveries of the time, as well as many religious beliefs such as the notion of Maat and Osiris, who became the most famous God during this period.

At the beginning of the Middle Kingdom

The twelfth dynasty began with the first Pharaoh of this dynasty, Amenemhat I, moving Egypt’s capital to a new city called Itjawy, possibly near the necropolis at Lisht. He was killed by his royal guard and his junior co-regent, his son Senuseret (1971 – 1926 B.C.E), took over the rule immediately, proving the efficiency of the co-regent system to Senuseret was able to preserve wealth and security for 45 years and reclaim all of the areas lost during the first intermediate period. His son, Amenemhat II (1929 BCE – 1895 BCE), was able to establish commercial relations with Nubia and re-establish the nomarchs’ rule. His successor, Senusret II (1897 BCE – 1878 BCE), established trade links with Palestine and the Levant, who was followed by Senusret III (1878 BCE – 1839 BCE), a fierce warrior-king who led his army across Nubia, where he built many forts across the country and many temples in Egypt that have since been devoured by time. These enchanted temples may be seen on a Nile river trip between Luxor and Aswan in the Nile Valley. Finally, Amenemhat III (1860 B.C.E. – 1815 B.C.E. ), the last pharaoh of the Middle Kingdom of Egypt, increased mining operations in the Sinai desert and exploited the Fayyum area to balance the difference between population and food production, and after his death, the Middle Kingdom Egypt came to an end.

The Middle Kingdom’s End

The thirteenth and fourteenth dynasties are believed to be the time when a disorderly fall of civilization began and the foreigner settlers from the East known as the Hyksos “Hika-Khasoot” began to gain greater influence in Egypt since the Hyksos were already dominating Egypt at the beginning of the second intermediate period.