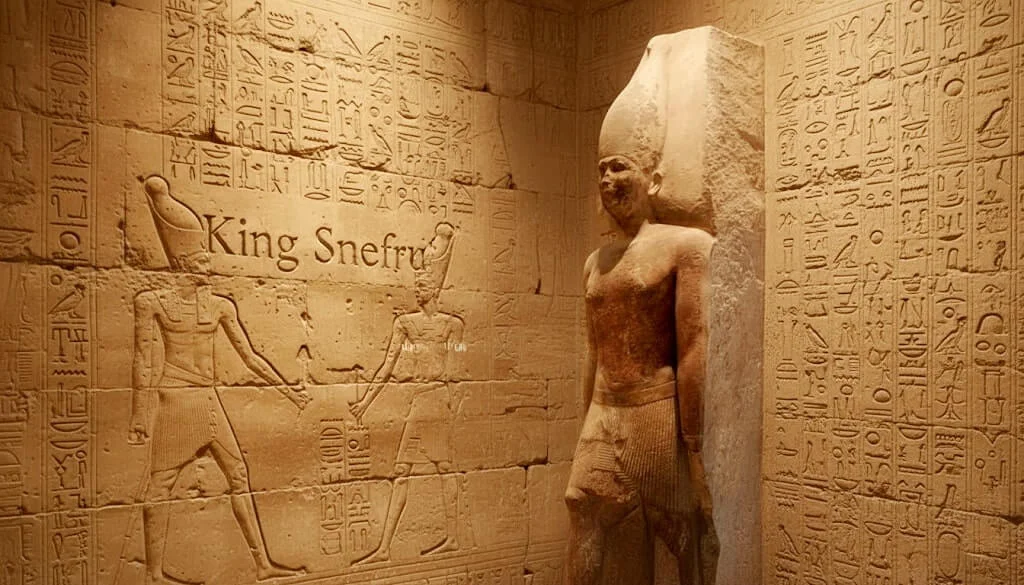

Heb-Sed Festival: A Journey to Rejuvenation

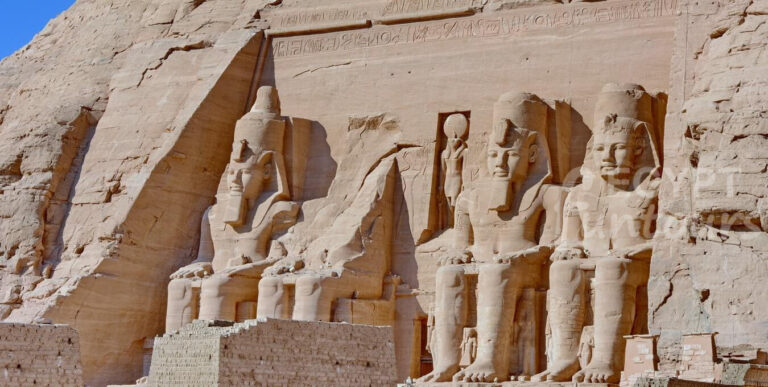

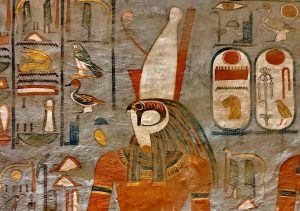

Ancient Egypt was a land of rich rituals and deep symbolism. Among the most important ceremonies was the Heb-Sed Festival, a jubilee that aimed to rejuvenate the pharaoh’s power and confirm his divine right to rule. This ancient celebration, steeped in tradition, played a crucial role in maintaining stability and prosperity throughout the kingdom.