The Five Main Historical Stages

The Ancient Egyptian Language was not static; it evolved dramatically across four thousand years, mirroring the rise and fall of dynasties and the continuous transformation of Egyptian culture. Scholars categorize this evolution into five primary historical stages, each defined by distinct grammatical features, vocabulary, and literary genres.

A. Archaic Egyptian (Before 2600 BCE)

The Archaic phase represents the earliest stage of the Ancient Egyptian Language that we can partially reconstruct. It corresponds with the late Predynastic Period and the two Dynasties of the Early Dynastic Period. We know this phase primarily through the earliest surviving hieroglyphic inscriptions, which appear on funerary stelae, seals, and ceramics, such as the elaborate Naqada II ceramic vessels.

These early writings typically consist of short labels, names, titles, and brief administrative notes. They focus intensely on record-keeping and identifying ownership. While the texts are too sparse to fully map out the grammar of Archaic Egyptian, they clearly demonstrate that the fundamental principles of the hieroglyphic script—the combination of logograms (word signs) and phonograms (sound signs)—were already in place. This phase laid the linguistic foundation for the massive literary and religious output that followed.

B. Old Egyptian (2600–2000 BCE)

Old Egyptian served as the official language of the Old Kingdom and persisted through the turmoil of the First Intermediate Period. This period produced a significant expansion of the language’s attested record, notably within monumental religious architecture.

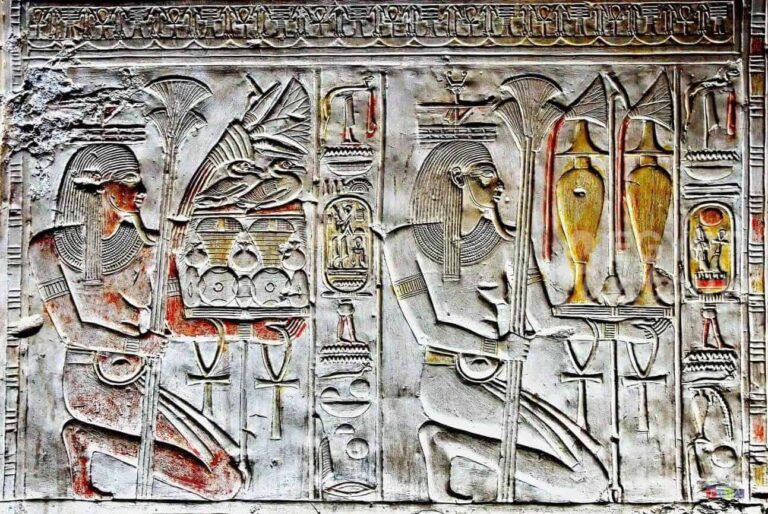

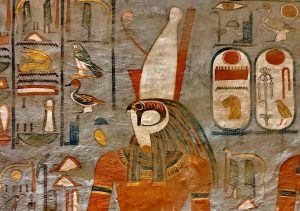

The largest and most important body of literature from this phase is the Pyramid Texts. These complex religious texts—inscribed on the interior walls of the pyramids of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasty pharaohs—detail the spells and rituals necessary to guide the deceased ruler’s spirit to the afterlife and ensure his resurrection among the stars. The language of the Pyramid Texts is dense, archaic, and often challenging to translate, reflecting the sacred and profound nature of the subject matter.

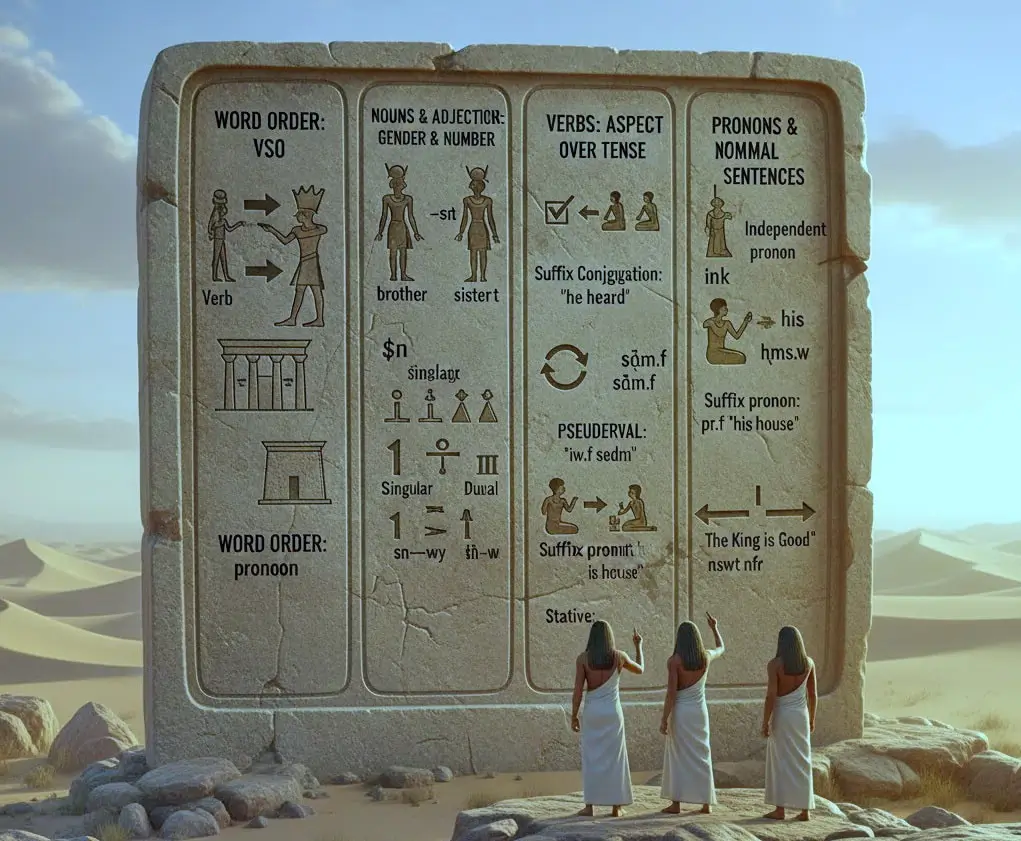

Grammatically, Old Egyptian was more conservative than later stages. The script consistently employed ideograms (pictures that represent the object itself), phonograms, and determinatives (silent signs that clarify the meaning of a word). Non-religious texts, such as tomb autobiographies and decrees, also began to appear, actively portraying the deeds and lives of important Old Kingdom officials.

C. Middle Egyptian (2000–1300 BCE)

Middle Egyptian is universally considered the Classical Egyptian Language. Although it was primarily the spoken language only during the Middle Kingdom, it gained such prestige that scribes continued to write in this dialect long after it had ceased to be vernacular—a parallel to the status of Latin in medieval Europe.

The literary breadth of Middle Egyptian is stunning. Scribes used it to create a massive corpus of diverse textual writings in both the hieroglyphic and the cursive Hieratic scripts. These texts include:

- Mortuary Texts: The Coffin Texts, which transferred the democratization of the afterlife from the pharaoh to commoners.

- Wisdom Literature: Philosophical and moral guides, like the Instructions of Amenemope, offering advice on how to live a virtuous life that aligned with the ancient Egyptian metaphysical concept of Maat (truth, order, balance).

- Scientific and Medical Documents: Important works like the Edwin Smith Papyrus documented surgical procedures and anatomical knowledge.

- Narrative Adventures: Literary works, such as The Tale of the Shipwrecked Sailor and The Story of Sinuhe, chronicled the fictionalized adventures of individuals, demonstrating the language’s capacity for complex storytelling.

Because the grammar and style of Middle Egyptian were so powerful and widely taught, it remained the standard for classical inscription for centuries, creating a deliberate archaism in later historical works.

D. Late Egyptian (1300–700 BCE)

Late Egyptian emerged during the New Kingdom, the apex of ancient Egyptian civilization, and became the language of everyday discourse. The New Kingdom was a cosmopolitan age of empire, and the language adapted, displaying a clear linguistic break from the older stages. The gap between Middle and Late Egyptian is grammatically much larger than the change observed between Old and Middle Egyptian.

Late Egyptian actively introduced new grammatical features and constructions, many of which resembled the spoken language more closely. The most noticeable shift involves the verb structure; the language began to rely less on synthetic verb forms and more on analytical constructions (using auxiliary verbs and particles). Its vocabulary also absorbed numerous loanwords, particularly from Semitic languages, due to Egypt’s extensive military and trade involvement in the Near East.

The literary output of this period is rich in both historical and creative works, including detailed accounts of major military campaigns (like the battles of Kadesh and the Delta), secular poetry, love songs, and complex spiritual passages. Scribes often intentionally mixed Late Egyptian with older classical forms, creating classicisms in historical and literary works to elevate their status, while the hieroglyphic orthography itself underwent a massive increase in its graphemic inventory (the number of available signs).

E. Demotic and Coptic (600 BCE – 17th Century CE)

The final two stages of the Ancient Egyptian Language saw dramatic changes, influenced heavily by foreign rule and the rise of Christianity.

1. Demotic Language (600 BCE – 400 CE):

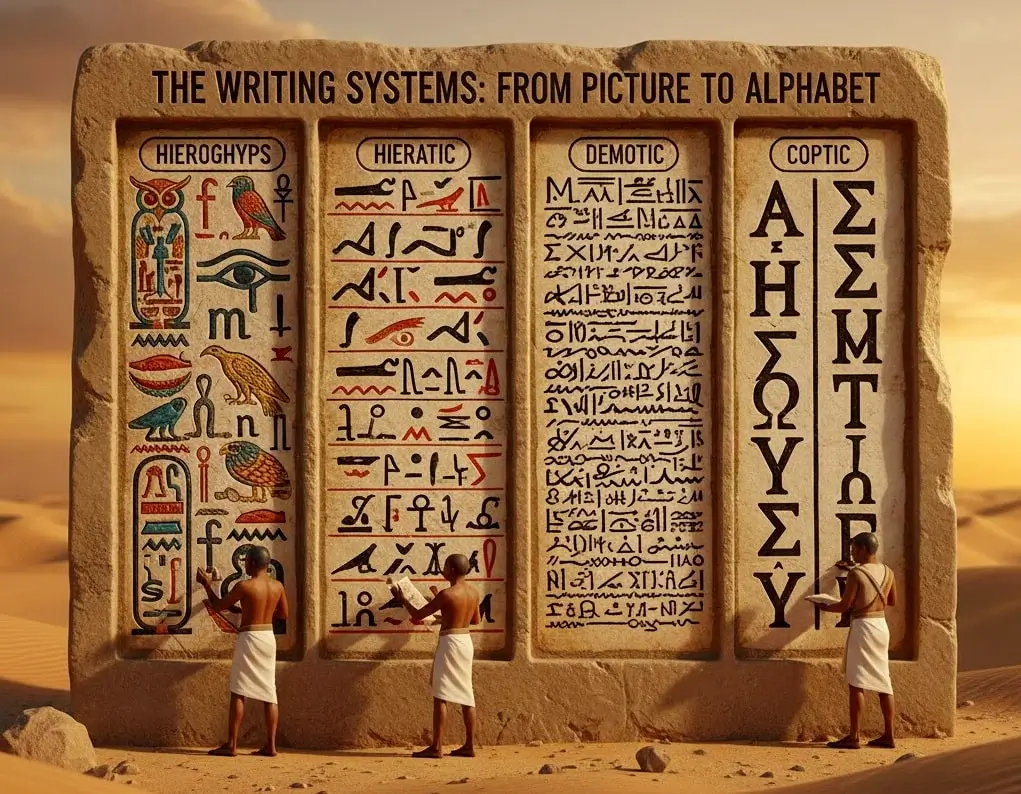

Demotic (meaning ‘popular’) was the vernacular language and highly cursive script of the Late and Ptolemaic periods, lasting for about 1,000 years. It evolved directly from the northern forms of the Hieratic script.

- The Early Demotic Language (650–400 BCE): This phase was primarily used for administrative, legal, and commercial writings, especially during the 26th Dynasty.

- The Middle Demotic Language (400–30 BCE): This stage saw widespread use for literary and religious compositions. However, the government officially adopted Greek as the language of administration following Alexander the Great’s conquest.

- Late Roman Demotic (30 BCE – 400 CE): Demotic texts began to decline as Greek dominance increased. Nonetheless, important religious works and temple graffiti, like the inscriptions on the temple walls of Goddess Isis on Philae, still attest to its use during the Roman era.

2. Coptic Language (200 – 1100 CE and beyond):

Coptic is the direct, last descendant of the Ancient Egyptian Language. It represents the definitive culmination of the linguistic transition, primarily serving as the official language from 200 CE onward. Crucially, Coptic abandoned the complex logographic and syllabic structures of earlier scripts and was written using a system based on the Greek alphabet, supplemented by seven extra letters borrowed from the Demotic script to represent sounds Greek lacked. Coptic was actively spoken until the 17th century. Today, it survives as the sacred liturgical language of the Coptic Orthodox Church, preserving the historical sounds and forms of the language for modern study.