The Enduring Significance of Abydos

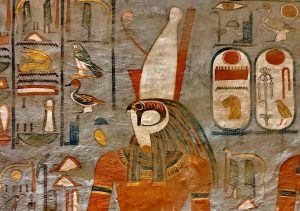

Abydos holds a unique status in Egypt. Indeed, it is one of the oldest and most sacred ancient sites. Consequently, its significance rests on two pillars. Firstly, it is the birthplace of royal funerary architecture (the Abydos Royal Tombs). Secondly, it functioned as the primary, revered cult center of Osiris (the spiritual heart of Egypt).

This double importance spans millennia. Thus, Abydos played a pivotal role from the Predynastic period straight through the New Kingdom. Therefore, exploring this Abydos Ancient Site is essential. We examine how the earliest kings defined their power here, and how a nation later sought eternal life in its holy soil.

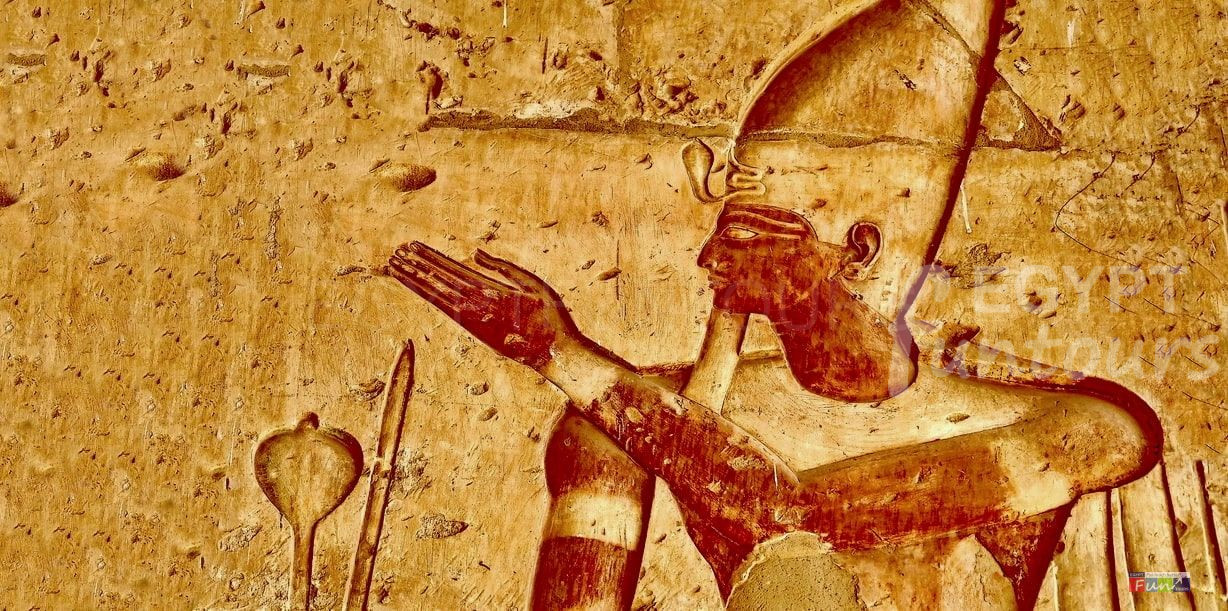

The Dawn of Dynasties: Abydos Royal Tombs (Umm el-Qa’ab)

Abydos first earned its prominence as a necropolis. Early burials here paved the way for grand royal traditions. Significantly, this site established the model for pharaonic interment.

A. Abydos Royal Tombs: Predynastic Precursors and Early State Formation

Predynastic burials laid the foundation for royal practices. Before the First Dynasty, the local elite chose this area, known as Cemetery U. Their simple graves signaled status differentiation. Importantly, early ritual activity focused on offering deposits. These deposits included fine pottery, ritual mace-heads, and foreign goods, such as Mesopotamian cylinder seals. Hence, the site quickly gained prestige as a preferred resting place, indicating early trade networks and wealth consolidation. Consequently, this established the conceptual groundwork for the later royal cemetery, demonstrating the merging of spiritual and political authority.

Crucially, Tomb U-j, dated to Naqada III (c. 3200 BCE), is often cited as belonging to an early ruler, possibly the legendary Scorpion King. Its significance rests on the hundreds of imported wine jars it contained. Furthermore, these jars held small bone and ivory tags bearing the earliest proto-hieroglyphic inscriptions. These labels recorded places of origin and quantities. Thus, the burial proves that sophisticated administration and taxation existed even before the formal First Dynasty.

B. Abydos Royal Tombs: The First Kings and Umm el-Qa’ab

The necropolis site is known today as Umm el-Qa’ab, meaning “Mother of Pots.” Crucially, it holds the tombs of Egypt’s earliest rulers, the true Abydos Royal Tombs. In fact, this includes the kings of Dynasties 0, I, and II. These tombs are vast, multi-chambered pits. Typically, they used wood and mudbrick construction, featuring internal storage rooms surrounding a central burial chamber.

Consider King Aha: His massive tomb complex consists of three chambers, labeled B10, B15, and B19. Furthermore, these burial sites contained thousands of jars. These jars held offerings of beer, wine, and food. Significantly, the tombs featured surrounding rows of smaller graves. These belonged to retainers, servants, and even dogs—evidence of human sacrifice, a practice quickly discontinued after the First Dynasty. Clearly, these structures signaled the king’s power over life and death, reinforcing the divine mandate of the pharaoh.

Moreover, the kings of Dynasty I, such as Djet, Den, and Queen Merneith, did not just build a subterranean tomb. They erected massive, freestanding funerary enclosures (or ‘forts’) approximately one mile away on the desert edge. These enclosures were ritual palaces for the Ka (spirit) of the king. Therefore, the site employed a dual system: the tomb for the body and the enclosure for the soul. This established the essential pattern of the royal mortuary complex for the next three millennia.

C. Abydos Royal Tombs: The Tomb of Khasekhemwy (Dynasty II)

The tomb of King Khasekhemwy marks a monumental transition, signaling the end of the Early Dynastic period. Specifically, his tomb (Tomb V) became the largest at Umm el-Qa’ab, measuring approximately 70 meters long. Uniquely, it stands out due to its immense size and elaborate mudbrick structure. Moreover, it contained a fully lined limestone burial chamber. This chamber is the earliest known use of cut stone for a funerary structure in Egypt. Thus, it acts as the direct architectural precursor to the step pyramid complex of Djoser.

Furthermore, Khasekhemwy’s funerary complex included a massive, separate enclosure, the Shunet ez-Zebib. This enclosure was over 120 meters long. Its walls, featuring buttresses and niches, mimicked the royal palace façade (serekh). Effectively, it represented his palace for eternity. Crucially, the funerary enclosures from the First and Second Dynasties are the last monuments built at Abydos exclusively for the living king’s worship before the shift to the Osiris cult. Ultimately, Khasekhemwy’s tomb represents a moment of architectural evolution, moving towards larger, more complex royal identity statements.