The Role of Music and Chantresses (Women in the Temple)

Music was a necessary part of all temple rituals. It was not just entertainment. Music had a specific Function. It helped to calm the volatile gods. It summoned the presence of the deity. Music also purified the temple space.

The Importance of the Sistrum and Menat in Ritual

The primary instruments were the sistrum and the menat. The sistrum was a sacred rattle. Its shaking warded off evil forces. The sound also pleased the goddess Hathor. The menat was a heavy bead necklace with a counterpoise. Priests and priestesses rattled it rhythmically. Both instruments were vital to the performance of temple rites. They created a necessary ritual soundscape.

Women held important religious roles in the temple. Chantresses (Šm’yt) were highly valued. They often belonged to elite families. They served the divine wives of the gods. Their Function was singing and playing instruments. They provided the necessary ritual music and dance. The most powerful women held the title God’s Wife of Amun. This office was deeply influential, especially during the New Kingdom.

Selection, Training, and Purity Requirements

Serving the gods required a rigorous system of selection and discipline. The priesthood was not open to everyone. It demanded lifelong dedication to Purity and Knowledge. The priests had to be flawless to maintain the connection with the divine.

Recruitment and Inheritance of Priestly Titles

Priestly positions often passed down through families. Sons frequently followed their fathers into temple service. This created powerful, generations-long priestly dynasties. Royal appointment also played a key role. The Pharaoh ultimately had the right to select or dismiss any priest. This ensured loyalty to the throne. High-ranking titles were often given to the king’s favored officials. This mixed system kept the priesthood both hereditary and politically controlled.

Rotation System and Part-Time Priesthood

Most priests were not full-time employees. They worked under a rotation system known as a Phyle (or sa). The staff was typically divided into four groups. Each phyle served for one month out of every four. They lived at the temple only during their month of service. For the other three months, they returned to their normal lives. This rotation allowed the temple to maintain a constant staff. It also allowed priests to manage their outside careers, showing the practical Function of the system.

Education and Scholarly Training

A priest’s training emphasized scholarship and rote learning. Temple schools were the centers of advanced Knowledge in Egypt.

Scribal Arts, Theology, and Temple Schools

The Scribal Arts were fundamental. Every priest needed to read and write the sacred hieroglyphs fluently. They trained extensively in the temple schools (Per-Ankh or “House of Life”). Students memorized vast amounts of literature. This included theological texts, rituals, hymns, and mythological narratives. This rigorous training ensured the perfect execution of their ritual Function. They became the keepers and interpreters of the oldest Egyptian wisdom.

The Strict Rules of Ritual Purity

Purity was the most critical requirement for temple service (PFK). A priest could not approach a god in a state of impurity. These rules were strict and constantly observed.

Diet Restrictions (Avoiding Fish and Pork)

Priests observed strict dietary laws. They avoided certain animals, such as fish and pork. They considered these foods impure or associated with the chaotic god Seth. Wine was also sometimes restricted inside the temple walls. Their carefully controlled diet kept their bodies ritually clean.

Personal Hygiene: Shaving All Body Hair and Frequent Bathing

Ancient Egyptian priests maintained extreme personal hygiene. They shaved all body hair, including their heads and eyebrows and performed this to prevent any form of lice or dirt. They also bathed in the temple’s sacred pool (Wabet) multiple times a day. Frequent washing ensured absolute ritual Purity before any service.

Clothing and Materials (Wearing Only Clean White Linen)

Priestly clothing was strictly regulated. They wore only clean, unstitched white linen. Animal skins, except for the leopard skin worn by the Sem Priest, were usually forbidden. Wool and leather were considered ritually impure. Their simple, clean garments symbolized their separation from the mundane world.

Sexual Abstinence During Temple Service

Sexual abstinence was required during their service month. Priests could not engage in sexual relations while on their Phyle duty. They needed to maintain spiritual Purity to interact with the divine power of the sanctuary. They lived as consecrated celibates only while inside the temple walls.

Economic and Political Influence

The temples of Egypt were vast economic and political entities, not just places of worship. The priesthood commanded enormous resources, granting them power that often rivaled the state bureaucracy. Their influence rested on wealth and control of Knowledge.

Temples as Economic Powerhouses

Temples functioned as the largest economic institutions in Egypt. They acted as major centers of wealth. Pharaohs endowed the gods with immense estates, making the temples rich and self-sustaining.

Ancient Egyptian priests owned vast amounts of land and livestock. Taxes and royal gifts further enriched the treasury. The Temple of Amun at Karnak, for instance, controlled hundreds of thousands of acres. Its economic Function was vital to the national economy. The priesthood managed a massive workforce of scribes, artisans, and farmers. The High Priest acted as a corporate executive, overseeing accounting and resource allocation. They were skilled bureaucrats who ensured the continuous flow of wealth.

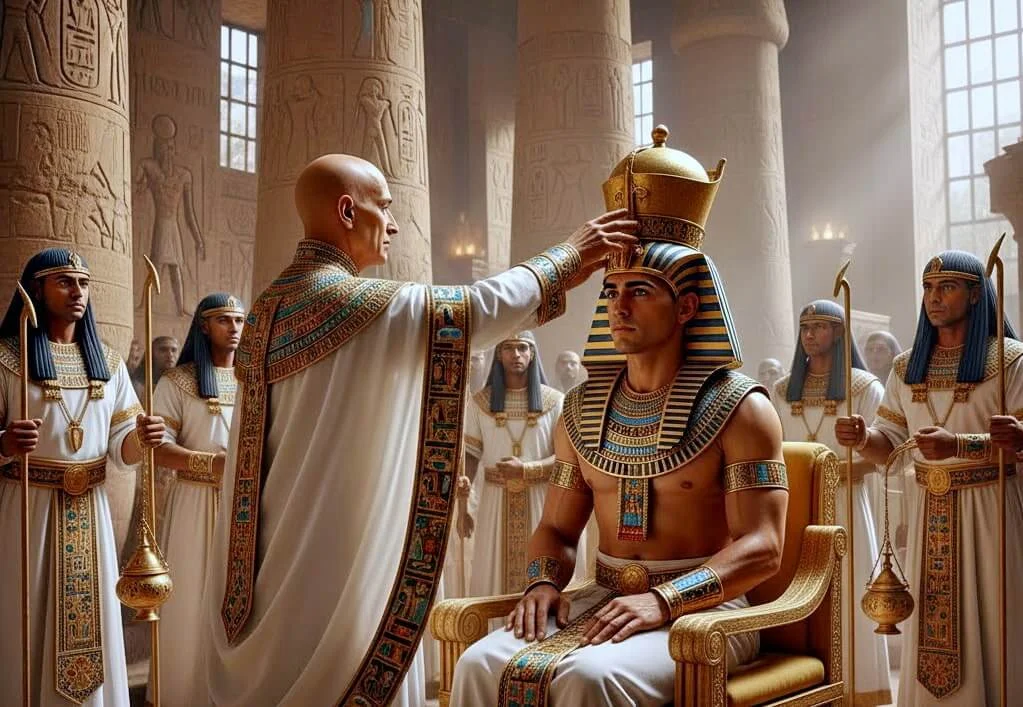

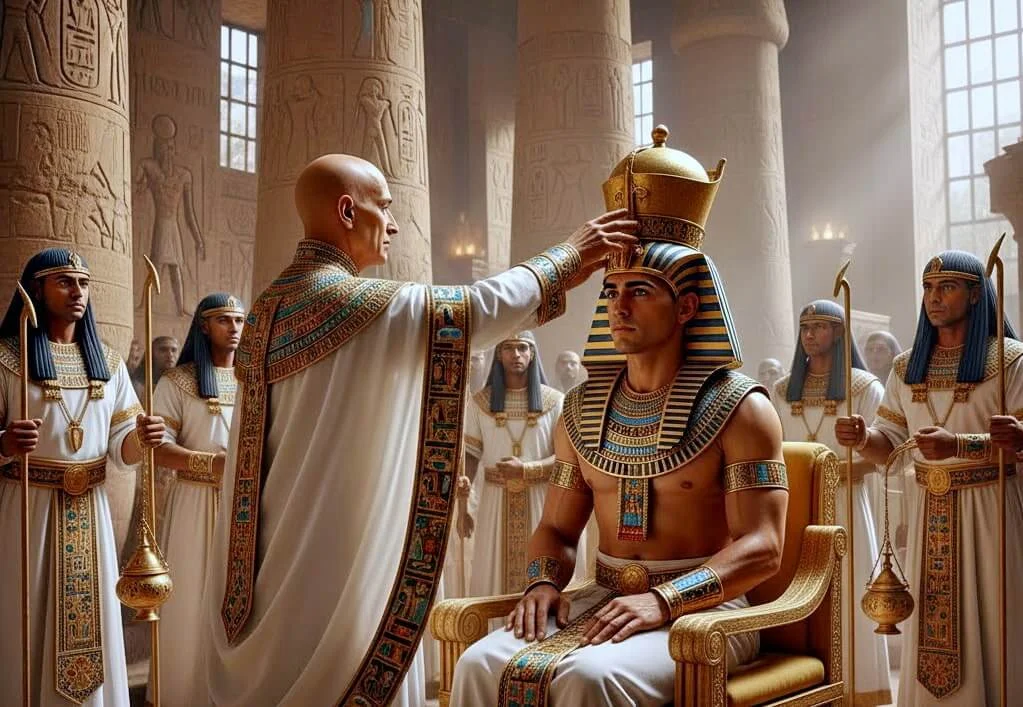

The Priesthood and the Pharaoh

The relationship between the priests and the king was a complex balance of dependence and tension. Priests needed royal support, but the Pharaoh needed them for divine legitimacy.

Priests were vital for establishing the Pharaoh’s right to rule. They performed the coronation rituals, which transformed the human king into a divine ruler. This cemented the Pharaoh’s role as the supreme mediator of Ma’at.

Tension often led to conflict. During the Amarna Period, Pharaoh Akhenaten directly challenged priestly power. He closed the temples of Amun and confiscated their wealth to promote the sole worship of the Aten. This attack failed; the priests successfully restored the old order after his death. The power of ancient Egyptian priests peaked in the Third Intermediate Period (c. 1070–712 BCE). The High Priest of Amun seized political control of Upper Egypt, ruling as a dynasty and commanding armies—they became kings in all but name.