The Sphinxes of Tanis: Guardians of the North

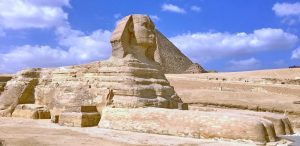

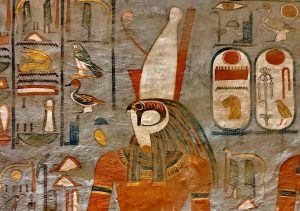

The Sphinxes of Tanis are a remarkable group of ancient Egyptian statues. They are a testament to the city’s power and its complex history. These sphinxes are not as famous as the Sphinx of Giza, but they are just as significant. They offer a unique window into a later period of Egyptian history, specifically the Ramesside and Third Intermediate Periods. The city of Tanis, located in the Nile Delta, was once a thriving royal capital. These sphinxes were its powerful guardians.