The Amarna Style: A Revolution in Art

Akhenaten’s religious revolution demanded an artistic one. His new theology was based on Ma’at—a concept of “truth” or “living in truth.” He wanted to move away from the old, idealized, and timeless art that focused on a perfect afterlife. Therefore, he needed a new art form to capture the raw, living, and imperfect “truth” of the present.

This radical new art form was the Amarna Style, and it shattered millennia of artistic tradition.

What Defines Amarna Art? (The Key Characteristics)

The Amarna Style is immediately recognizable and completely distinct from all other periods of Egyptian art. Its key characteristics were a direct reflection of Akhenaten’s new religion.

Intimacy and Family: The most profound change was the focus on the royal family’s personal life. For the first time, artists showed the pharaoh in candid, affectionate, and unguarded moments. We see Akhenaten and Nefertiti kissing their daughters, holding them on their laps, or openly mourning the death of a child. This intimate look at the pharaoh’s life was a complete break from the formal, god-like imagery of the past.

Expressive Realism (or “Exaggeration”):

The Amarna Style is most famous for its unique and often unsettling portrayal of the human body. Artists abandoned the idealized, athletic forms of old and instead portrayed figures with:

- Elongated heads and slender, curving necks.

- Thin arms and limbs.

- Protruding bellies, wide hips, and full, pronounced lips.

Scholars still debate the meaning of these features. Were they a form of “expressionism,” or was this “realism” an accurate portrait of the royal family, who perhaps had a genetic condition? Many believe it was a new theological statement, creating an androgynous “father and mother” look for the pharaoh, who, like the Aten, was the sole creator of all life.

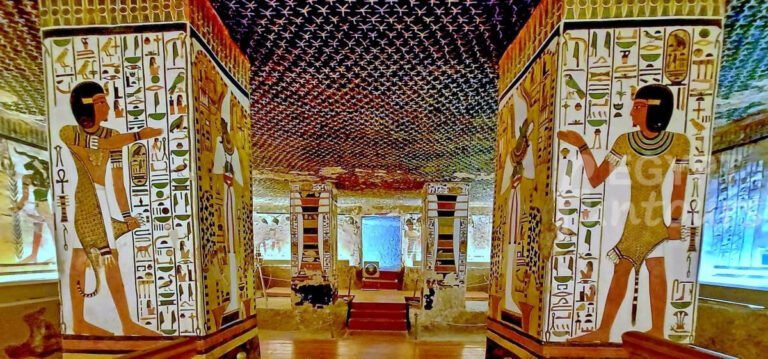

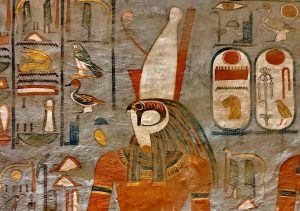

The Sun-Disc: A defining feature of the Amarna Style is the constant presence of the god. In almost every relief and painting, the Aten floats at the top as a sun-disc. Its long rays, ending in small human hands, reach down to the royal family, extending the ankh (the symbol of life) exclusively to Akhenaten and Nefertiti. This visual perfectly reinforced their unique position as the sole connection to the divine.

Masterpieces of the Amarna Period

Beyond the iconic Nefertiti Bust, sculptors and artists produced other masterpieces of the Amarna Style.

The colossal statues of Akhenaten, which he erected at a temple in Karnak early in his reign, show the style in its most exaggerated form. They are intentionally jarring, designed to shock the viewer and announce the arrival of a pharaoh who was completely different.

Perhaps most illustrative of the Amarna Style are the small, private altar pieces found in the city of Akhetaten. These detailed reliefs, like the one showing the royal family in an intimate domestic scene, combine all the key elements: the elongated features, the tender family moment, and the life-giving rays of the Aten shining down upon them all.

The Royal Children: A Famed Son and Lost Daughters

The intimate family scenes of the Amarna Style were not just an artistic choice; they were a core part of the new religion. Akhenaten and Nefertiti put their children front and center in their new world, a striking departure from the formal, distant portraits of pharaohs past.

The Six Daughters of Akhenaten and Nefertiti

Akhenaten and his Great Royal Wife, Nefertiti, had six daughters: Meritaten, Meketaten, Ankhesenpaaten (who would later become the famous wife of Tutankhamun, Ankhesenamun), Neferneferuaten Tasherit, Neferneferure, and Setepenre.

Artists frequently depicted these princesses in remarkably casual and affectionate scenes—sitting on their parents’ laps, playing, or being kissed. This constant reinforcement of “family” was central to the worship of the Aten, the giver of all life and fertility. Tragically, the second daughter, Meketaten, appears to have died young. Reliefs from the royal tomb at Amarna show Akhenaten and Nefertiti grieving her death—a raw, human, and heartbreaking display of emotion never before seen in royal art.

The “Boy King”: The Link to Tutankhamun

For decades, the parentage of Egypt’s most famous pharaoh, Tutankhamun, remained one of history’s greatest mysteries. However, groundbreaking DNA testing in 2010 provided a stunning and definitive answer.

The tests confirmed that Tutankhamun was the son of Akhenaten. He was born at the height of the Atenist revolution, and his original name was Tutankhaten, meaning “Living Image of the Aten.”

This discovery also solved another puzzle: who was his mother? The same DNA study revealed that his mother was not Queen Nefertiti. Instead, she was another of Akhenaten’s wives, a woman whose mummy archaeologists discovered in tomb KV35 and now know only as the “Younger Lady.”

This young prince, born as Tutankhaten, would soon be thrust from the isolation of his father’s desert city onto the world stage, where he would play the starring role in undoing his father’s entire revolution.

The Fall of the Amarna Revolution

Akhenaten’s entire religious and cultural world was built on his own divine authority. It was a vision so personal that it could not survive without him. Consequently, the moment he died, the revolution began to crumble.

Akhenaten’s Death and the Aftermath

After a 17-year reign, Akhenaten died. The period immediately following his death is one of the most chaotic and confusing in Egyptian history.

He was briefly succeeded by one or two mysterious rulers, known as Neferneferuaten (who may have been Nefertiti) and Smenkhkare. Their reigns were short and unstable. In effect, without its charismatic and fanatical founder, the great city of Akhetaten had lost its purpose. The experiment was failing, and the old powers were waiting in the wings.

The Return to Tradition: Tutankhamun’s Restoration

After the brief, shadowy reigns of Akhenaten’s successors, the throne fell to his nine-year-old son, the boy-prince Tutankhaten.

As a child, powerful and traditional-minded advisors—like the vizier Ay and the General Horemheb—guided his every move. Almost immediately, they began the “Great Restoration,” a systematic undoing of his father’s entire life’s work.

- The Name Change: The first and most symbolic act was to change their names. Tutankhaten (“Living Image of the Aten”) became Tutankhamun (“Living Image of Amun”). His young wife, Akhenaten’s daughter Ankhesenpaaten, became Ankhesenamun. This was a public declaration that Amun was back.

- Abandoning the City: The royal court abandoned Akhetaten, the “Horizon of the Aten,” and moved the capital back to the traditional centers of power, Thebes and Memphis. Akhenaten’s desert city was left to the sun and the sand.

- The Restoration Stela: Tutankhamun soon issued a royal decree, known today as the Restoration Stela. This remarkable document describes Egypt as a nation in chaos, claiming his father’s revolution had angered the gods. It details how the temples had fallen into ruin and the gods had “turned their backs” on Egypt. The stela then proudly proclaims how Tutankhamun reopened the temples, re-funded the priesthoods, and restored the old gods to their rightful places.

Damnatio Memoriae: Erasing the Heretic King

This restoration did not satisfy the pharaohs who followed. They saw the Amarna period as a shameful, heretical scar on Egypt’s history. Later pharaohs, like Horemheb and Ramesses II, launched a campaign of Damnatio Memoriae—a “damnation of memory.”

This was not simple neglect. It was a deliberate, systematic attempt to erase Akhenaten from history. Workers descended on Akhetaten and his other temples and tore them down. They smashed his statues and used the stone blocks, now called talatat, as filler for their own new temple pylons. Most thoroughly, they chiseled Akhenaten’s face and name off every monument they could find.

Scribes carved new official king lists in later temples. These lists skipped directly from Akhenaten’s father (Amenhotep III) to Horemheb. They pretended Akhenaten, Nefertiti, and Tutankhamun had never existed. This effort was successful for thousands of years. The “heretic king” was all but forgotten.