The Map to Eternity: The Book of the Dead

Perhaps the most famous element of ancient Egyptian burial rituals is the Book of the Dead. However, it was not a single, standardized book, and that was not its real name.

The ancient Egyptians called it Ru nu peret em hru, or The Book of Coming Forth by Day. It was a collection of over 200 magical spells, hymns, and instructions written on a papyrus scroll, which was rolled up and placed in the coffin. It served as the ultimate personalized guidebook for the afterlife. A wealthy person’s scroll would be long and beautifully illustrated; a poorer person might only have a few key spells written on their coffin.

The spells provided the deceased with the secret knowledge needed to navigate the treacherous landscape of the Duat, overcome monstrous guardians, know the secret names of gods and gatekeepers, and even transform into different powerful animals.

The Climax: The Weighing of the Heart Ceremony

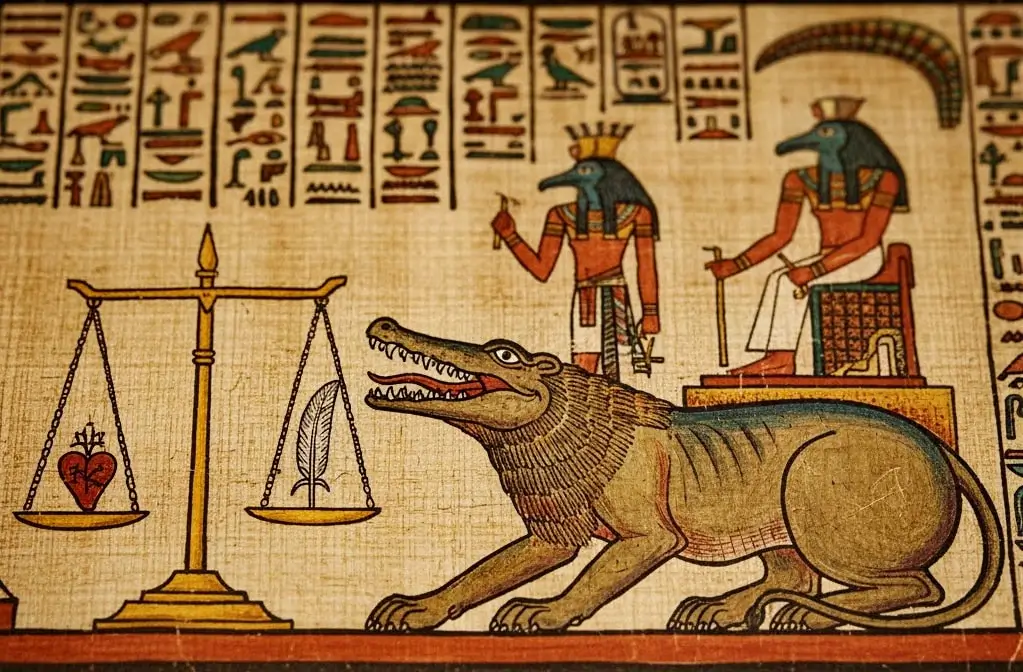

Spell 125 in the Book of the Dead describes the soul’s most critical test: the Weighing of the Heart. In this final judgment, the gods determined if a soul was worthy of eternal life. The entire dramatic scene unfolds in the Hall of Two Truths:

1. The Test

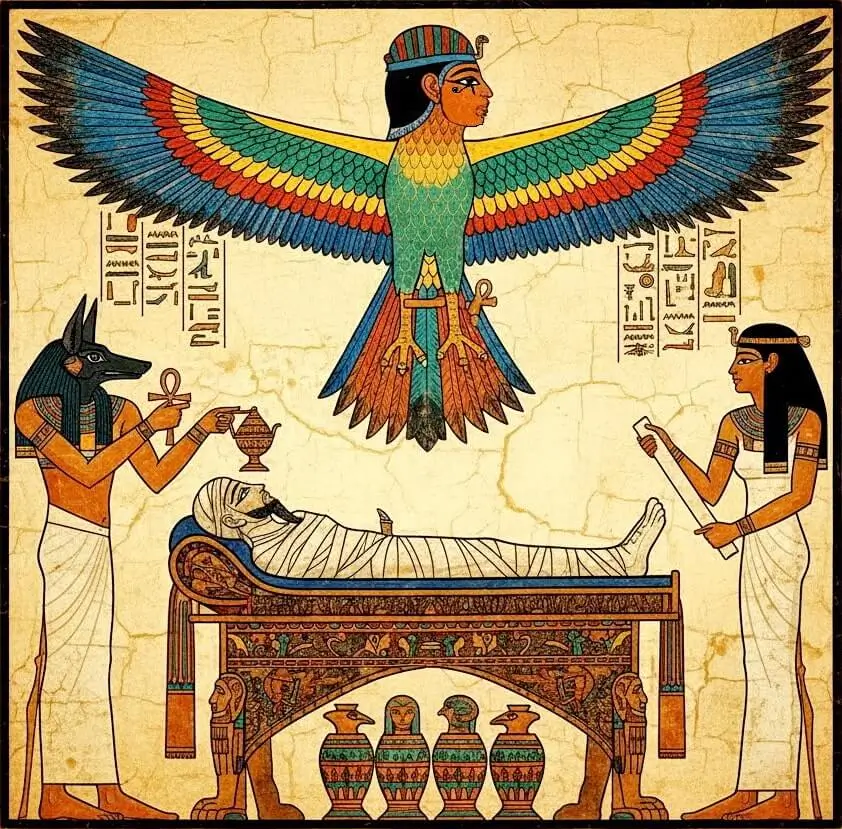

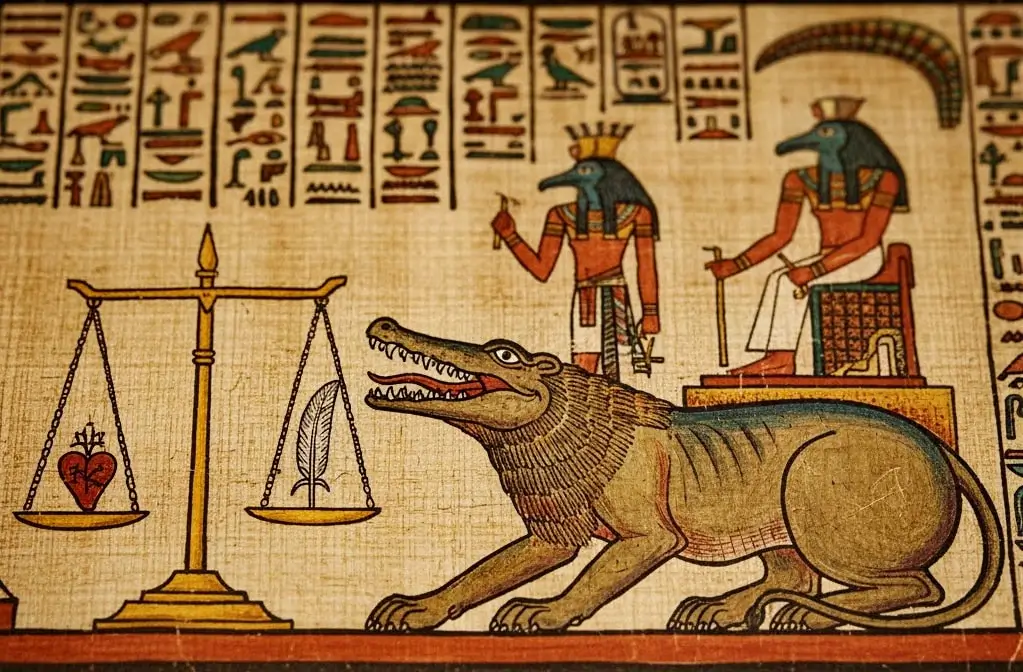

First, a god leads the deceased spirit before Osiris, the great god of the underworld. The jackal-headed god Anubis then takes the person’s heart, the Ib, and places it on one side of a great golden scale.

2. The Measure

On the other side of the scale, Anubis places a single, pure white feather. This is the Feather of Ma’at, the goddess who represents truth, justice, and cosmic order.

3. The Declaration

The deceased must then declare their innocence by reciting the “Negative Confession.” They have to prove they are free from sin with statements such as: “I have not committed robbery,” “I have not killed,” “I have not told lies,” “I have not been deaf to the words of truth,” and “I have not made anyone weep.” These confessions give us a remarkable insight into Egyptian morality.

4. The Verdict

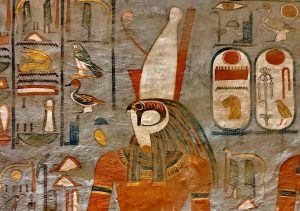

If the heart balances with the feather, or is even lighter, it proves the person lived a righteous life. The gods then declare the soul “true of voice” (maa-kheru). Thoth, the ibis-headed scribe of the gods, steps forward to record this just verdict.

5. The Consequence

However, if a heart heavy with sin tips the scales, the soul faces annihilation. The monstrous goddess Ammit, the “Devourer of the Dead”—a terrifying hybrid of a crocodile, lion, and hippopotamus—waits eagerly by the scales. The gods throw the sinful heart to Ammit, and she devours it. The soul then suffers the “second death,” ceasing to exist forever. For an ancient Egyptian, this complete oblivion was the ultimate terror.

Passing this final test unlocked the gateway to an eternity of bliss in the Field of Reeds.

The Funeral Procession: The Final Public Journey

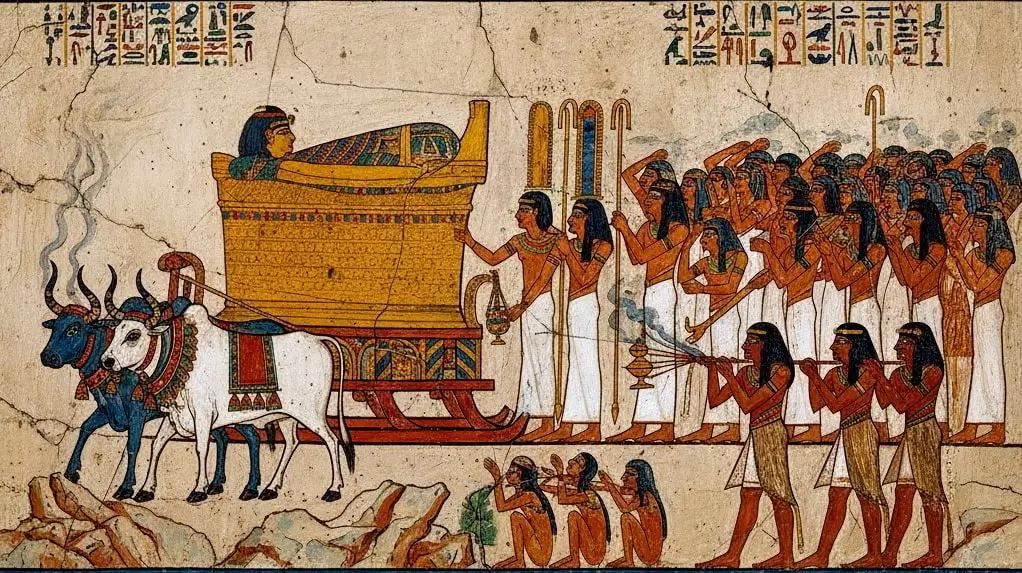

The actual funeral was a public and dramatic affair. A grand procession would carry the coffin from the deceased’s home to the Nile. Mourners, including family and professional mourners (women paid to weep, throw dust on their hair, and lament loudly), would follow.

The coffin was ferried across the Nile to the West Bank, the traditional land of the dead where the sun set. From the riverbank, attendants placed the coffin on an ox-drawn sledge and dragged it to the tomb. Priests walked alongside, burning incense and chanting prayers. The procession often included mysterious figures like the Tekenu, a person wrapped in animal skins whose exact role Egyptologists still debate. As they reached the entrance, special dancers known as the “Muu dancers” performed their ritual dance.

Once the priests completed the “Opening of the Mouth” ceremony, attendants carried the coffin into the burial chamber. They arranged the grave goods around the sarcophagus and sealed its heavy lid. Finally, stonemasons sealed the tomb’s entrance, intending for it to remain untouched for eternity.